Developer Offer

Try ImaginePro API with 50 Free Credits

Build and ship AI-powered visuals with Midjourney, Flux, and more — free credits refresh every month.

Beyond the Lens Truth in Scientific Photography

A new book, Flashes of Brilliance: The Genius of Early Photography and How It Transformed Art, Science, and History by Anika Burgess, is a beautifully written love letter to the power of the photographic image. It serves as a witty and personal meditation on how images do far more than just document a scene.

This book highlights the dual role of a scientific image: it's both a tool for discovery and a medium for communication. It helps us understand that photography, especially in science, is not merely illustrative but deeply investigative. As Burgess clearly describes, it can sometimes be truly revelatory.

The Investigative Power of a Photograph

Through compelling stories and visual examples, the book reminds us that an image can crystallize a complex idea in a way words often cannot. It’s a celebration of those ‘aha’ moments made visible, waking us up to social issues and phenomena we never knew existed.

Take, for example, Jacob Riis’ images from around 1889, which documented the squalid conditions of people in New York City’s tenements. By using flash powder to illuminate these gloomy spaces, he revealed details about the inhabitants' lives that spoke volumes more than any written description could.

When Images Deceive The Challenge of Manipulation

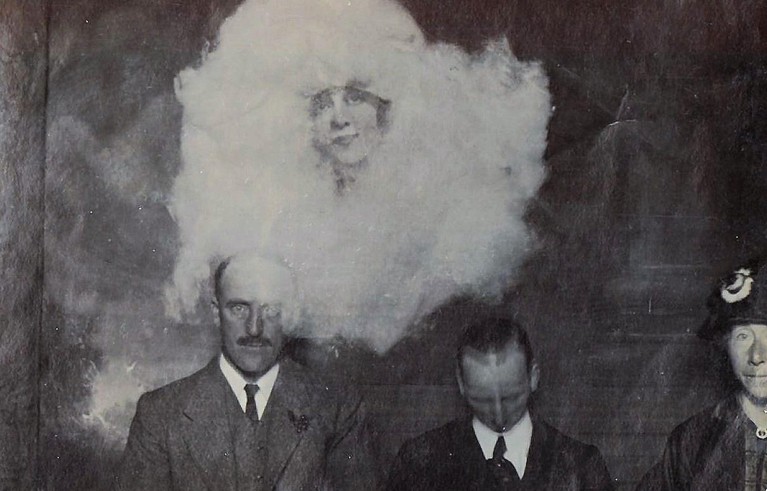

Burgess doesn't shy away from the challenges, acknowledging how easily images can mislead or manipulate. From the very beginning of photography, some practitioners combined negatives to create unreal scenarios. In the early 1870s, Édouard Buguet famously used this technique to insert translucent ‘spirits’ into portraits, convincing many that the dead could communicate from beyond the grave. He only admitted the images were fake in 1875.

The book also provides another surprising example from the work of Eadweard Muybridge. While his iconic sequences of horses in motion from the 1870s proved that all four hooves leave the ground during a trot, the book reveals a lesser-known fact. Muybridge would sometimes substitute, omit, and renumber certain images, which calls their scientific utility into question. As historian Marta Braun argued, Muybridge, under the guise of scientific truth, arranged his selection to present his own personal truth.

Navigating the Line Between Clarity and Truth

For anyone involved in science communication, this is an essential warning. The balance between clarity and accuracy is a constant challenge, and any manipulation must be carefully considered and disclosed. Muybridge's work could have been seen as a more authentic scientific investigation if he had informed us of his process, much like how NASA scientists explain how and why they colour astronomical images.

This resonates with Susan Sontag’s famous argument in On Photography that “to photograph is to appropriate the thing photographed.” Images allow our minds to accept what we are seeing as reality. The early image-makers featured in Flashes of Brilliance were not just documenting the world but transforming it into something permanent and possible.

Whether it’s Cecil Shadbolt’s aerial photographs of London from a balloon or Louis Boutan’s captures of life beneath the sea, these images are never neutral. They actively shape what we believe is true about the world and what we consider worth looking at.

Compare Plans & Pricing

Find the plan that matches your workload and unlock full access to ImaginePro.

| Plan | Price | Highlights |

|---|---|---|

| Standard | $8 / month |

|

| Premium | $20 / month |

|

Need custom terms? Talk to us to tailor credits, rate limits, or deployment options.

View All Pricing Details