Developer Offer

Try ImaginePro API with 50 Free Credits

Build and ship AI-powered visuals with Midjourney, Flux, and more — free credits refresh every month.

AI Helps Unmask Nazi Killer in Infamous Holocaust Photo

A Haunting Image, A Decades-Old Mystery

It is one of the most disturbing and iconic images of the Holocaust: a bespectacled Nazi soldier points a pistol directly at the head of a man in a suit, who kneels resignedly before a pit filled with bodies. For decades, this chilling photograph, mistakenly titled “The Last Jew in Vinnitsa,” was an anonymous testament to the horrors of the era, its subjects and location shrouded in mystery.

Now, thanks to the tireless work of a historian and the power of modern technology, a key part of that mystery has been solved. US-based German historian Jürgen Matthäus has spent years piecing together the puzzle and, with the help of artificial intelligence, has confidently identified the killer.

The Long Road to Identification

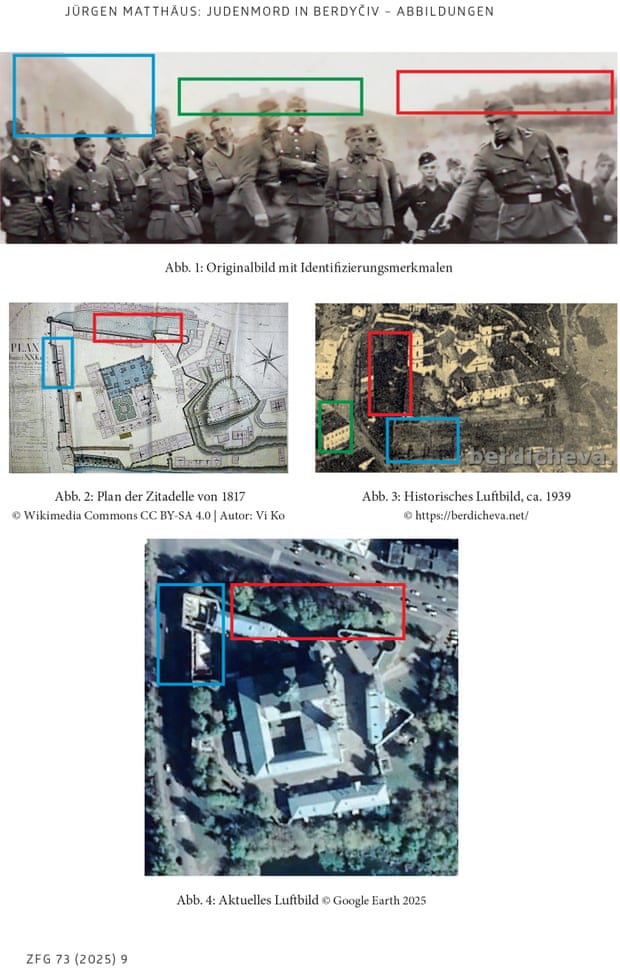

Matthäus’s research, published in the academic periodical Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaft (Journal of Historical Studies), first corrected the long-held inaccuracies surrounding the photograph. The massacre did not take place in Vinnytsia, but rather in the citadel of Berdychiv, Ukraine, a city that was once a thriving center of Jewish life. The date was pinpointed to July 28, 1941.

The perpetrators were members of the Einsatzgruppe C commando, one of the mobile SS death squads deployed to eliminate “Jews and partisans” in the occupied Soviet Union, just days before a visit from Adolf Hitler. Through a combination of archival research, lucky breaks, and peer collaboration, Matthäus was building a clearer picture of the event. But the identity of the gunman remained elusive.

How AI Cracked the Case

The crucial breakthrough came after Matthäus published his preliminary findings about the date and location, which generated media coverage in Germany. A reader contacted him, suggesting the man with the pistol could be his wife’s uncle, Jakobus Onnen, based on family letters from that period.

While the letters themselves had been destroyed, family photos of Onnen survived. This is where cutting-edge investigation techniques came into play. Matthäus collaborated with volunteers from the open-source journalism group Bellingcat, who used the photos to conduct an AI-powered image analysis.

“The match, from everything I hear from the technical experts, is unusually high in terms of the percentage the algorithm throws out there,” Matthäus explained. While historical photos make a 99.9% match difficult, the strong likeness, combined with the extensive circumstantial evidence, provided the credibility needed to identify the killer.

Matthäus noted the growing potential for AI in historical research: “Digital tools in the humanities have massively increased in use, but it’s usually for the processing of mass data, not so much for qualitative analysis. This is clearly not the silver bullet – this is one tool among many. The human factor remains key.” Photograph: Metropol

Who Was the Killer, Jakobus Onnen?

Jakobus Onnen was not a high-ranking officer but a French, English, and gym teacher born in 1906. He came from an educated family and had joined the Nazi party before Hitler came to power in 1933. His participation in such atrocities did not lead to any special promotion; he was killed in battle in August 1943.

Matthäus believes the photo was taken by a fellow soldier and that Onnen was posing for the camera. Such gruesome snapshots were often treated as “trophies” from civilian massacres. “The reason I think why he is posing there, the way he depicts himself – I think is meant to impress,” Matthäus said.

Jakobus Onnen, who had joined the Nazi party before Hitler took power in 1933, came from an educated family. Photograph: Metropol

The Face of Evil: Why This Discovery Matters

This investigation does more than just name a killer. It reinforces the brutal, hands-on nature of the Holocaust in the east, a reality often overshadowed by the industrialized killing at camps like Auschwitz. “I think this image should be just as important as the image of the gate in Auschwitz, because it shows us the hands-on nature, the direct confrontation between killer and person to be killed,” Matthäus stated.

The existence of photos like this, sent home by soldiers, also debunks the myth that the German population was unaware of the genocide being committed.

The work is not over. Matthäus is now collaborating with a Ukrainian colleague, Andrii Mahaletskyi, to uncover the identity of the victim in the suit. Using Soviet-era records and potentially AI analysis, they hope to restore the name of one of the more than one million Jews murdered in the occupied Soviet Union, whose identities, as Matthäus says, remain unknown, “just as the killers intended.”

Compare Plans & Pricing

Find the plan that matches your workload and unlock full access to ImaginePro.

| Plan | Price | Highlights |

|---|---|---|

| Standard | $8 / month |

|

| Premium | $20 / month |

|

Need custom terms? Talk to us to tailor credits, rate limits, or deployment options.

View All Pricing Details